Introduction

As geopolitical tensions rise around the production and supply of Rare Earth Elements (REEs), Vietnam and its international partners are presented with an opportunity to exploit its reserves and emerge as one alternative supplier to China. Recent regulatory and policy updates indicate that the government is serious about this prospect. However, certain technological and infrastructure hurdles remain.

This blog is the third in our series: “Shaping Asia’s Infrastructure”, which explores legal developments shaping infrastructure across Asia. This update investigates Vietnam’s place in the global REE market and discusses the opportunities and challenges ahead for companies seeking to invest in the country’s nascent REE sector.

Background and industry structure

The 17 REEs, typically divided by atomic weight into ‘light’[1] and ‘heavy’[2] REEs, are essential components in a broad range of modern technology. Notably, REEs are used in the production of permanent magnets, which are critical inputs for data storage, renewable energy, medical, automotive and consumer electronic products.

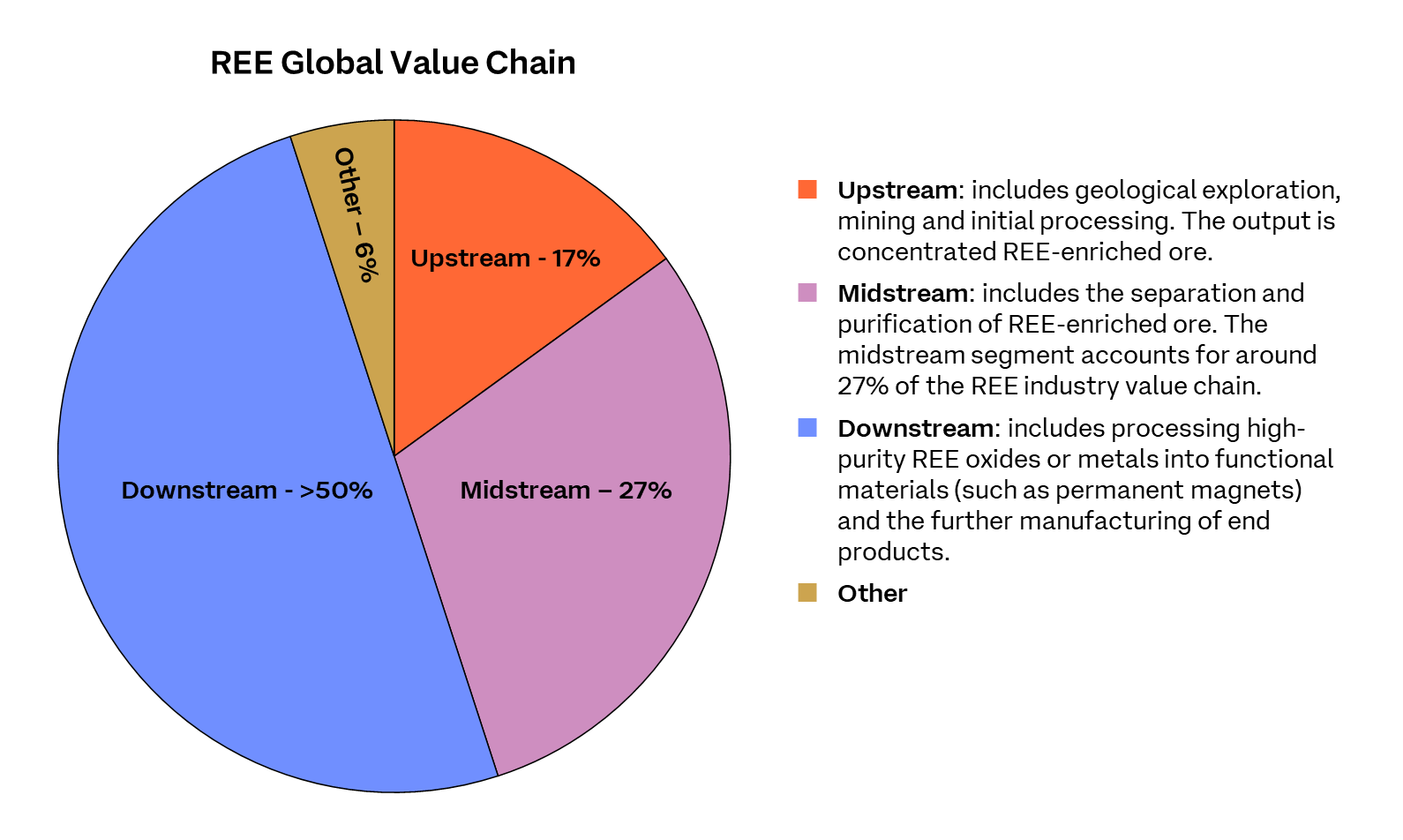

The REE industry can be broadly divided into three sections:

Source: Vietnam Rare Earth Industry Research Report 2025-2034 (Research and Markets)

Whilst not geologically rare (global REE reserves are estimated to be more than 400 times the current annual production), extraction and processing is technologically complex and environmentally challenging.

Currently, China is dominant throughout the supply chain, accounting for 70% of REE ore upstream extraction and around 90% of midstream/downstream processing. 94% of the world’s permanent magnets are made in China. China’s dominance in the industry has been achieved through early and consistent state investment, export controls, low labour costs and lenient environmental law enforcement.

Trade tensions and supply chain diversification

Global REE supply has become a key focal point this year, as tensions around supply from China compound with ever-increasing global demand for rare earth products.

In April 2025, in apparent retaliation against President Trump’s proposed trade tariffs, China imposed licensing requirements on the export of seven REEs and magnets, requiring US and EU companies to obtain additional licenses before exporting from China. The resulting alarm from industry leaders around potential production delays was a poignant reminder of China’s dominance over the global supply chain.

Six months later in October, China expanded its export restrictions, requiring foreign companies to obtain export approvals for products: (i) containing even trace amounts of Chinese-origin REEs; (ii) made using Chinese REE technology; or (iii) produced outside of China incorporating Chinese origin materials or technology. These restrictions mirrored the US’ foreign direct product rule, which places restrictions on third-country exports to China of semiconductor-related products incorporating US technology or components.

Despite an apparent de-escalation at the US-China trade meeting at the end of October, these events have brought the question of REE supply into sharp focus for governments and businesses around the world. The result has been a notable shift in US and EU strategy to de-risk from China. For example:

- At the ASEAN summit in October 2025, the US announced cooperation deals with Malaysia and Thailand to promote trade and investment in critical mineral resource extraction, processing and refining.

- Also in October, US-based manufacturer Noveon Magnetics announced its partnership with Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths for the supply of REE permanent magnets and the development of a REE value chain in the US.

- In September 2025, USA Rare Earth (USAR) announced its USD 100 million acquisition of Less Common Metals (LCM), a UK-based manufacturer of REE metals and alloys. The acquisition of LCM is a key step in USAR’s ‘mine-to-magnet’ strategy.

- In July 2025, the US Department of Defense entered into an agreement to become the largest shareholder in Mountain Pass, California (the US’ only operational REE mine) guaranteeing minimum prices for its neodymium and praseodymium output. The agreement also includes the creation of a new US facility to increase midstream/upstream processing capacity.

- In April 2024, the EU Commission adopted the Critical Raw Materials Act, which aims to minimise REE supply chain risk by: (i) strengthening strategic partnerships with resource-rich countries; (ii) promoting the development of domestic mining and processing capacities; (iii) increasing recycling rates and developing new technologies for critical minerals; and (iv) increasing investment in R&D to find alternative technologies to REEs.

REEs in Vietnam: opportunities

The REE issue should be viewed as a structural shift in global supply chains, rather than a short-term crisis to be resolved. In this context, Vietnam (having already demonstrated its strategic agility through the ‘China Plus One’ approach in the manufacturing sector) is well-positioned to seize new opportunities as global markets seek to diversify away from China’s rare earths dominance.

Vietnam is currently ranked sixth in the world for total REE reserves, with approximately 3.5 million tons.[3] While the REE industry in Vietnam is still in its early stages, ambitious policies and developing legal frameworks recognise Vietnam’s potential and have helped to provide a roadmap for the country’s REE vision. For example:

- Prime Minister Decision 866/QD-TTg 2023 (Decision 866) launched an implementation plan for exploration, exploitation, processing and use of minerals, offering tangible steps to achieve Vietnam’s goals of fostering a globally competitive REE industry. The strategy outlines long and short-term objectives for exploration, mining and processing:

- Exploration: by 2030, Vietnam aims to complete exploration schemes in Bac Nam Xe and Nam Nam Xe mines in Lai Chau, as well as carry out additional exploration, upgrading and expansion of sites in Lai Chau, Lao Cai and Yen Bai. During the 2031-2050 period, Vietnam aims to carry out additional exploration of licensed REE mines and explore additional mining sites.

- Mining: by 2030, Vietnam aims to accelerate its search for mining technologies and markets associated with deep processing of rare earth minerals at licensed mines such as Dong Pao (Lai Chau) and Yen Phu (Yen Bai). The plan additionally envisions total mining output for all mines to reach around two million tons of crude ore per year by 2030. During the 2031-2050 period, Vietnam aims to increase its total output by maintaining existing projects, expanding operations in the Dong Pao mine and investing in further mining projects in Lai Chau and Lao Cai.

- Processing: by 2030, Vietnam aims to complete investment in several new REE processing sites in Lai Chau and Lao Cai, with a view to processing 20,000-60,000 tons of REEs per year. During the 2031-2050 period, Vietnam aims to increase its REE processing output to 40,000-80,000 tons per year.

- Law No. 54/2024/QH15 on Geology and Minerals (2024 Geology and Mineral Law) was adopted on 29 November 2024 and took effect from 1 July 2025. It introduced significant changes to its 2010 predecessor, including classifying mineral resources into four defined groups and outlining the State’s responsibilities around geological exploration and exploitation.

- A draft amendment to the 2024 Geology and Mineral Law, scheduled to take effect in 2026, recognises the critical nature of REEs and proposes a separate framework for their management. Notably:

- The government acknowledges that REEs are “a special commodity, creating a great impact on national defense, security and diplomacy around the world.” The government states its goal of “creating a driving force for the development of the industry of exploitation, processing and use of rare earth minerals in a synchronous manner”, acknowledging that “it brings practical benefits to the country in the context of the world's current shortage of rare earth supplies.”[4]

- Importantly, “the State shall encourage international cooperation in research and development of technologies for exploitation, selection, separation and deep processing of rare earths in service of the development of the domestic rare earth industry.”[5]

- The draft amendment explicitly states that REEs “must not be exported crudely”, which reinforces the government’s focus on improving the country’s processing capabilities.”[6]

While the separate REE framework remains high-level at this stage (detailed, implementing decrees are expected to follow the draft amendment), Vietnam’s vision for the future of its industry as outlined above represents significant potential for international collaboration.

Indeed, Vietnam has already received interest in the REE space from multiple foreign investors, including:

- Blackstone Minerals and Australian Strategic Materials, two Australian mining companies, signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Vietnam Rare Earth JSC (VTRE) to facilitate cooperation in identifying, assessing and securing rare earth mining opportunities in Vietnam.

- LS Eco Energy, a subsidiary of South Korea’s cable and energy company LS Cable & System, announced it is seeking to establish a REE value chain in Vietnam.

- Posco International, a South Korean company, has indicated its interest in making further investments in Vietnam, including in REE processing.

- Trident Global Holdings, a South Korean investment company specialising in resource development, and Zoetic Global, a US technology provider, has indicated plans to establish a joint venture to co-develop premium REE mines in Vietnam.

One project receiving particular attention is the Dong Pao mine, a site ultimately controlled by State-run mining group Vinacomin. Having sat dormant for several years, Vinacomin is now reportedly soliciting strategic international partners again. Based on Vietnam’s current regulatory trajectory, we may expect to see many more such opportunities arising as the government finalises and implements its REE framework.

REEs in Vietnam: challenges

Despite forward-thinking policy, abundant REE reserves and high investor interest, Vietnam faces various challenges to meet its REE targets.

Vietnam has demonstrated its intentions to improve its processing capabilities and move up the REE value chain. However, while Decision 866 sets out ambitious processing targets, the financial, technical, environmental and operational requirements to achieve these remain immense. Stakeholders will need to be both proactive and patient.

Another challenge for Vietnam’s REE industry is recent corruption allegations against employees of two separate Vietnamese mining companies. The accompanying arrests stalled government plans to auction new rare earth mining concessions and cast a cloud of uncertainty over the industry which may take some time to clear.

Conclusion

Vietnam stands at a strategic crossroads in the global REE supply chain, boasting both abundant resources and political determination. With coordinated policy support and the right international partnerships, Vietnam could move beyond extraction to become a hub for high-value processing, building a competitive and lucrative rare earth industry.

[1] Including cerium, lanthanum, praseodymium, neodymium, promethium, europium, gadolinium and samarium.

[2] Including dysprosium, terbium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, yttrium and lutetium.

[3] Historic estimates previously placed Vietnam’s REE reserves at 22 million tons, the second largest after China, but this was amended by the US Geological Survey in March 2025.

[4] P. 10 of the Statement on the Draft Law Amending and Supplementing a Number of Articles of the Law on Geology and Minerals.

[5] Article 85a.3 of the Draft Law Amending and Supplementing a Number of Articles of the Law on Geology and Minerals.

[6] Article 85a.3 of the Draft Law Amending and Supplementing a Number of Articles of the Law on Geology and Minerals.

/Passle/5832ca6d3d94760e8057a1b6/MediaLibrary/Images/5caf47f7abdfea0b306b985f/2021-08-16-10-10-30-866-611a3996400fb311c899dbf1.jpg)