Joshua Kelly and Mariia Puchyna

China goes global – what is the Belt and Road Initiative?

As discussed in our 'Top Trends in International Arbitration for 2018', China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) offers a clear investment target for international companies looking to capitalise on China’s economic growth and plans for outbound investment. With over 70 jurisdictions in its scope, covering 65% of the world’s population and at least one-third of the world’s GDP, the BRI has the potential to become one of the world’s largest and most ambitious platforms for regional cooperation, solidifying China’s significant economic role in the 21st century.

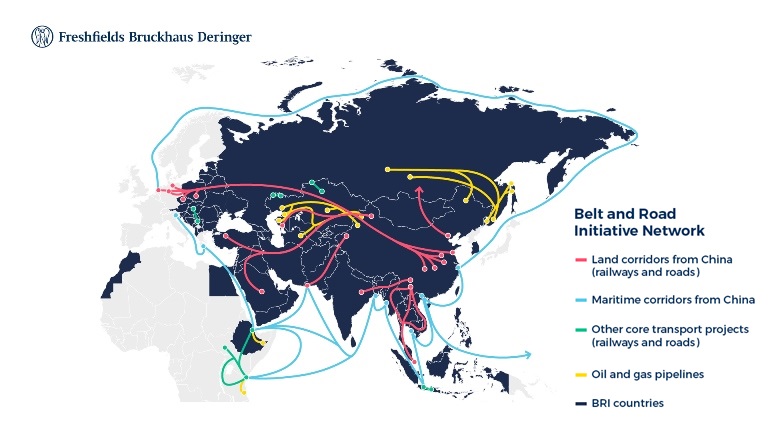

The BRI network

As the above map shows (click here for a full-size version), the BRI’s “belt” is a network of transport and other infrastructure projects designed to create economic land corridors from China through to Southeast Asia, Russia, Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. The BRI’s “road” comprises maritime links from China to western Europe via East Africa, the South Pacific Ocean via the South China Sea (also known as the “Pacific Silk Road”) and northern Europe across the top of Russia (also known as the “Polar Silk Road” or the “Silk Road on Ice”).

Beyond transportation links, major BRI infrastructure projects include oil and natural gas pipelines, power stations, utility grids, hydropower projects, windfarms, airports and the expansion of ports. A vast network of optic fibre cables is also being installed as part of an ambitious plan for a “Digital Corridor” (sometimes referred to as the “Digital Silk Road”) that will link BRI countries through cyberspace. BRI countries will also be joined to China’s new satellite-navigation services to create a “Space Information Corridor.”

Scope for growth

To date, more than US$1 trillion has been committed to thousands of BRI projects. In the long term, estimates of the total amount to be invested under the BRI reach up to US$10 trillion.

Over half of the BRI’s funding is being provided by the four main State-owned commercial banks of China, with significant contributions also coming from the China Development Bank and the Export Import Bank of China. In turn, these lenders are supported by a number of smaller but politically important development funds, such as the Silk Road Fund, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the BRICS-led New Development Bank.

Given the BRI’s focus on benefitting China, it should be no surprise that Chinese State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) have taken the lead as investors, with Chinese private entities not far behind. Despite this trend, opportunities abound for foreign investors as Chinese firms seek to partner up with international companies that can act as brokers, offer know-how and expertise, or provide access to markets that have previously been out of reach.

Investment protection and dispute resolution on the BRI

Before entering a BRI project, foreign investors will of course want to keep one eye on the steps they can take to anticipate and manage their legal risks. Some of the issues that should make it onto a BRI foreign investment checklist include:

1. Investment structuring

For international businesses, finding the ideal investment structure will require a careful analysis of the available corporate and shareholder structures to navigate tax treaty protection, national law restrictions and investment protection under international treaties (bilateral and multilateral) and foreign investment laws. These structuring considerations will need to be analysed alongside any proposals for a partnership or joint venture with stakeholders (such as State-owned entities) who may be able to offer jurisdiction-specific advantages.

2. MIGA insurance

Several countries that will benefit from the BRI have historically been exposed to economic and political instability. Given this risk, investors may also want to consider purchasing insurance from the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). MIGA offers insurance against losses relating to, among other things, currency inconvertibility and transfer restrictions, expropriation, war, terrorism and civil disturbance and political risk. MIGA also has the ability to link into the network of the World Bank Group, potentially enabling an insured investor to leverage those connections, if necessary.

3. Business and human rights

The high-risk/high-reward nature of some BRI jurisdictions means that investors will also need to turn their mind to issues of human rights, environmental protection, transparency, and corporate social responsibility (CSR), including where compliance with CSR standards is required for financing. To that end, the EU has urged China to put transparency, labour standards, debt sustainability, open procurement processes and the environment at the heart of the BRI. China has responded to these concerns by stressing that in BRI countries, Chinese companies will seek to develop local economies, increase local employment opportunities, and improve local living conditions. Some financial institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Silk Road Fund, and the New Development Bank, have also already made provision for compliance with CSR and human rights standards in their investment guidelines.

4. State and international organisation immunities

For private investors, the involvement of Chinese SOEs and development banks as either partners or lenders in a project will require a closer look at the potential immunities of these entities, and whether any waivers of those immunities should be sought. SOEs and development banks may be able to rely on State or international organisation immunities under international law and domestic laws. These immunities can be far-reaching, precluding lawsuits, execution of judgments, and/or interim relief (such as an injunction). Equally, Chinese SOEs and development banks may find that they need to agree to a full or partial waiver of their immunities to encourage foreign investment, or obtain financing. Where any of these issues are live, advice will be required to ensure that the risks are properly managed from the outset.

5. Choice of law

While there does not appear to be any consensus as to the law that will most likely be chosen by contracting parties in BRI projects, past trends suggest that local laws may be preferred where a government or a State-owned entity is involved. However, in principle (and subject to any requirements that may make the laws of the People's Republic of China mandatory) there is no reason why parties should not consider whether another system of law is more suitable. For example, the laws of England & Wales, Hong Kong or Singapore may enable parties from different jurisdictions to achieve certainty and predictability around the effect of their contractual terms, while maintaining their freedom to contract.

6. Dispute resolution: arbitration by default?

At its broadest, there are three types of disputes that are likely to arise out of BRI projects: (i) “pure” commercial disputes between entities engaged in BRI projects (most notably construction disputes); (ii) investment disputes between investors and States; and (iii) State-to-State trade and commercial disputes. Given the possibility of a BRI project giving rise to a dispute involving parties from other jurisdictions, it will be necessary to consider, at the outset of a project, how any dispute should be resolved, including whether there is any preference for litigation, arbitration or another form of dispute resolution. If litigation is preferred, it will also be necessary to consider which courts, if any, should have jurisdiction over a dispute (noting that China has established two specialist courts to address disputes arising out of the BRI).

The search for a dispute resolution mechanism that is culturally sensitive, flexible, impartial, relatively cost-efficient and supported by an international enforcement framework generally leads to one obvious choice: arbitration. As outlined in our 'Top Trends in International Arbitration for 2018', we anticipate an increase in the number of international arbitrations arising out of BRI projects. That prediction is supported by the historical preference of Chinese SOEs to use arbitration, especially where foreign investment is concerned. Where BRI-related international arbitrations are seated remains to be seen. However, China is working hard to promote its own arbitration centres. In late 2017, for example, the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) adopted its own arbitration rules on “International Investment Disputes”, intended for use in relation to BRI disputes.

Of course, foreign investors are likely to insist on international dispute resolution centres with experienced supervisory courts, such as Paris, Hong Kong, Singapore, London and the Dubai International Financial Centre. To that end, the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) have been developing services to address BRI disputes and improve awareness about arbitration, with Freshfields partner John Choong being appointed as one of the Ambassadors to the ICC's Belt and Road Commission. Other dispute resolution centres such as the Dubai International Financial Centre-London Court of International Arbitration Centre or the newly established Astana International Financial Centre Court are also likely to see an increased number of disputes arising out of BRI projects.

Mariia Puchyna and Joshua Kelly are associates in the international arbitration group of Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP.

/Passle/5832ca6d3d94760e8057a1b6/MediaLibrary/Images/2024-12-19-08-27-41-006-6763d8fdda543fe5c20b0fae.png)